Message From Our President

Dear Students, Faculty, Staff and Friends,

I am pleased to present to you this Guide to our plans for the upcoming fall semester and reopening of our campuses. In form and in content, this coming semester will be like no other. We will live differently, work differently and learn differently. But in its very difference rests its enormous power.

The mission of Yeshiva University is to enrich the moral, intellectual and spiritual development of each of our students, empowering them with the knowledge and abilities to become people of impact and leaders of tomorrow. Next year’s studies will be especially instrumental in shaping the course of our students’ lives. Character is formed and developed in times of deep adversity. This is the kind of teachable moment that Yeshiva University was made for. As such, we have developed an educational plan for next year that features a high-quality student experience and prioritizes personal growth during this Coronavirus era. Our students will be able to work through the difficulties, issues and opportunities posed by our COVID-19 era with our stellar rabbis and faculty, as well as their close friends and peers at Yeshiva.

To develop our plans for the fall, we have convened a Scenario Planning Task Force made up of representatives across the major areas of our campus. Their planning has been guided by the latest medical information, government directives, direct input from our rabbis, faculty and students, and best practices from industry and university leaders across the country. I am deeply thankful to our task force members and all who supported them for their tireless work in addressing the myriad details involved in bringing students back to campus and restarting our educational enterprise.

In concert with the recommendations from our task force, I am announcing today that our fall semester will reflect a hybrid model. It will allow many students to return in a careful way by incorporating online and virtual learning with on-campus classroom instruction. It also enables students who prefer to not be on campus to have a rich student experience by continuing their studies online and benefitting from a full range of online student services and extracurricular programs.

In bringing our students back to campus, safety is our first priority. Many aspects of campus life will change for this coming semester. Gatherings will be limited, larger courses will move completely online. Throughout campus everyone will need to adhere to our medical guidelines, including social distancing, wearing facemasks, and our testing and contact tracing policies. Due to our focus on minimizing risk, our undergraduate students will begin the first few weeks of the fall semester online and move onto the campus after the Jewish holidays. This schedule will limit the amount of back and forth travel for our students by concentrating the on-campus component of the fall semester to one consecutive segment.

Throughout our planning, we have used the analogy of a dimmer switch. Reopening our campuses will not be a simple binary, like an on/off light switch, but more like a dimmer in which we have the flexibility to scale backwards and forwards to properly respond as the health situation evolves. It is very possible that some plans could change, depending upon the progression of the virus and/or applicable state and local government guidance.

Before our semester begins, we will provide more updates reflecting our most current guidance. Please check our website, yu.edu/fall2020 for regular updates. We understand that even after reading through this guide, you might have many additional questions, so we will be posting an extensive FAQ section online as well. Additionally, we will also be holding community calls for faculty, students, staff and parents over the next couple of months.

Planning for the future during this moment has certainly been humbling. This Coronavirus has reminded us time and time again of the lessons from our Jewish tradition that we are not in full control of our circumstances. But our tradition also teaches us that we are in control of our response to our circumstances. Next semester will present significant challenges and changes. There will be some compromises and minor inconveniences--not every issue has a perfect solution. But faith and fortitude, mutual cooperation and resilience are essential life lessons that are accentuated during this period. And if we all commit to respond with graciousness, kindness, and love, we can transform new campus realities into profound life lessons for our future.

Deeply rooted in our Jewish values and forward focused in preparing for the careers and competencies of the future, we journey together with you, our Yeshiva University community, through these uncharted waters. Next year will be a formative year in the lives of our students, and together we will rise to the moment so that our students will emerge stronger and better prepared to be leaders of the world of tomorrow.

Best Wishes,

Ari Berman

He understood that as a coach, he was an educator. He understood that as an educator, he was a mentor. He understood that as a mentor, he was taking these young men on a journey for which his life experience had uniquely prepared him. Each of his players came away from those seasons not only as better players but as better men who understood that there was so much more to a decision than just the immediate result and to treat everyone they encountered with respect and to engage people in meaningful conversation. One of his players recounted that “in his Principles of Management class, Professor Tufts would emphasize—even as a CEO of a company—the importance of treating the doorman or janitor just as well as you would the CFO.”

As a student in the YU EMBA program, I had the privilege to sit with him weekly and delve into business decisions that companies made. Going back to school in my mid-40s meant that it had been 25 years since I had written academic papers, but Bob made my experience easier and profound. He would sit on the front of the desk, look us each in the eye and get us to figure out why companies made decisions. Any professor can come at that from the perspective of profit and loss, but Bob wanted us to understand the larger significance of the decision, the larger societal impact, the larger ethical rationale. We would talk after class until Security kicked us out and then in front of the building until I realized that if I wanted to stay married, I had to hurry back home.

It was in those talks that I heard about his other life: his advocacy for patient rights, his life of baseball, his life as a proud Jew, his life of cancer. I learned what it was like to pitch in the majors and everything—both challenging and wonderful—that came along with it. I learned about what kind of man Ben Carson was and what is was like to work at HUD. I learned he had a daughter who worked in sports marketing, and he would give me a wry smile each time I asked if she wanted to come work for me for less money and a horrible boss. His eyes would light up when we talked of those women.

There are so many of us who are richer for having known Bob Tufts and poorer for losing him. We should hang on to the things that stayed with us, hang on to the smiles we shared with him and hang on to the things that make us chuckle that are completely inappropriate to speak of in polite company. He will always have a special place in my heart and a permanent place in our program.

Bob was a great colleague, a true gentleman and a very dedicated teacher. It is hard to believe that I will not run into him in the hallways or chat with him in my office. May his memory be a blessing through the stories we share, and may we always be grateful that we had Robert Tufts in our lives.

He understood that as a coach, he was an educator. He understood that as an educator, he was a mentor. He understood that as a mentor, he was taking these young men on a journey for which his life experience had uniquely prepared him. Each of his players came away from those seasons not only as better players but as better men who understood that there was so much more to a decision than just the immediate result and to treat everyone they encountered with respect and to engage people in meaningful conversation. One of his players recounted that “in his Principles of Management class, Professor Tufts would emphasize—even as a CEO of a company—the importance of treating the doorman or janitor just as well as you would the CFO.”

As a student in the YU EMBA program, I had the privilege to sit with him weekly and delve into business decisions that companies made. Going back to school in my mid-40s meant that it had been 25 years since I had written academic papers, but Bob made my experience easier and profound. He would sit on the front of the desk, look us each in the eye and get us to figure out why companies made decisions. Any professor can come at that from the perspective of profit and loss, but Bob wanted us to understand the larger significance of the decision, the larger societal impact, the larger ethical rationale. We would talk after class until Security kicked us out and then in front of the building until I realized that if I wanted to stay married, I had to hurry back home.

It was in those talks that I heard about his other life: his advocacy for patient rights, his life of baseball, his life as a proud Jew, his life of cancer. I learned what it was like to pitch in the majors and everything—both challenging and wonderful—that came along with it. I learned about what kind of man Ben Carson was and what is was like to work at HUD. I learned he had a daughter who worked in sports marketing, and he would give me a wry smile each time I asked if she wanted to come work for me for less money and a horrible boss. His eyes would light up when we talked of those women.

There are so many of us who are richer for having known Bob Tufts and poorer for losing him. We should hang on to the things that stayed with us, hang on to the smiles we shared with him and hang on to the things that make us chuckle that are completely inappropriate to speak of in polite company. He will always have a special place in my heart and a permanent place in our program.

Bob was a great colleague, a true gentleman and a very dedicated teacher. It is hard to believe that I will not run into him in the hallways or chat with him in my office. May his memory be a blessing through the stories we share, and may we always be grateful that we had Robert Tufts in our lives.

Ken Davidoff, Bob Tufts (Courtesy of Ken Davidoff)

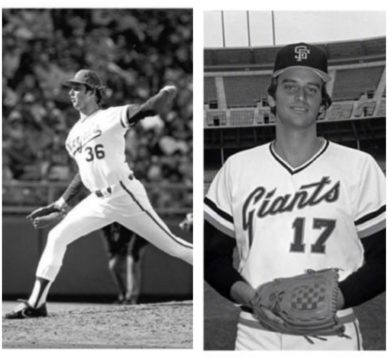

Ken Davidoff, Bob Tufts (Courtesy of Ken Davidoff) Sy Syms Professor Bob Tufts is a former Major League Baseball pitcher. In addition to teaching sports management at Sy Syms, he coaches pitching for the men's baseball team at Yeshiva University.

Sy Syms Professor Bob Tufts is a former Major League Baseball pitcher. In addition to teaching sports management at Sy Syms, he coaches pitching for the men's baseball team at Yeshiva University. Tufts in his Major League days.

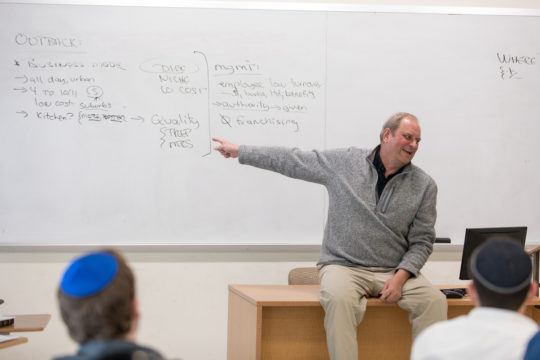

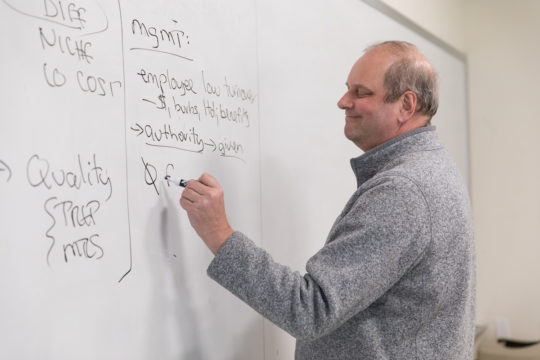

Tufts in his Major League days. Bob Tufts doing what he loved to do: teach

Bob Tufts doing what he loved to do: teach These days, Tufts leads a busy life along with his teaching. He never really left the world of baseball even after he retired. He has served as president of the New York State Chapter of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association and conducted baseball clinics in Cooperstown for Jewish Major Leaguers, Inc. and in Israel for the Israel Association of Baseball. He has written columns on baseball for Examiner.com, editorials on sports for major newspapers and an essay for the ESPN book Fathers and Daughters and Sports. He has also appeared as a panelist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, the Yogi Berra Museum, the 92nd Street Y, Temple Emanu-El, the Museum of Jewish Heritage and the Isabella Freedman Center.

This year, Tufts also volunteered as a pitching coach for YU's men's baseball team. “He was really helpful,” said Greg Fox, associate athletics director, “and he’s also a really great guy.”

Tufts also is also a

These days, Tufts leads a busy life along with his teaching. He never really left the world of baseball even after he retired. He has served as president of the New York State Chapter of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association and conducted baseball clinics in Cooperstown for Jewish Major Leaguers, Inc. and in Israel for the Israel Association of Baseball. He has written columns on baseball for Examiner.com, editorials on sports for major newspapers and an essay for the ESPN book Fathers and Daughters and Sports. He has also appeared as a panelist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, the Yogi Berra Museum, the 92nd Street Y, Temple Emanu-El, the Museum of Jewish Heritage and the Isabella Freedman Center.

This year, Tufts also volunteered as a pitching coach for YU's men's baseball team. “He was really helpful,” said Greg Fox, associate athletics director, “and he’s also a really great guy.”

Tufts also is also a